The Old Oak is a beacon of hope and humanity for our troubled times. If it turns out to be Ken Loach’s swansong he leaves us with a typically passionate and heartfelt collaboration. Pub landlord TJ and refugee Yara work together to battle poverty and racism in their local County Durham community, showing how kindness, photography and food can help bring people together. If this solidarity occasionally feels too idealistic for our broken times, we can forgive Loach and screenwriter Paul Laverty for dialling down the bleakness of I, Daniel Blake. They are still raging against government-imposed misery, injustice and division. But the culture-crossing friendship shown in The Old Oak, based on real-life events, offers us a way forward.

A black and white filmshow-within-the-film beautifully encapsulates the director’s cinematic vision, recalling the monochrome images of his first issue-based dramas such as Cathy Come Home (1966). This scene shows us the power of film to bring ordinary people together, not just for escapism, but also to celebrate themselves.

Set in 2016, the year of the Brexit vote, the film opens with a coachful of Syrian refugees arriving in a small ex-mining community in the Northeast. They are met with hostility from a mob of locals. A young man wearing a Newcastle United shirt is enraged that one of the refugees (Yara, played by Ebla Mari) is taking photos. He snatches the camera from her and accidentally breaks it. TJ (Dave Turner) acts as peacemaker; he befriends Ebla and becomes a bridge between the two communities.

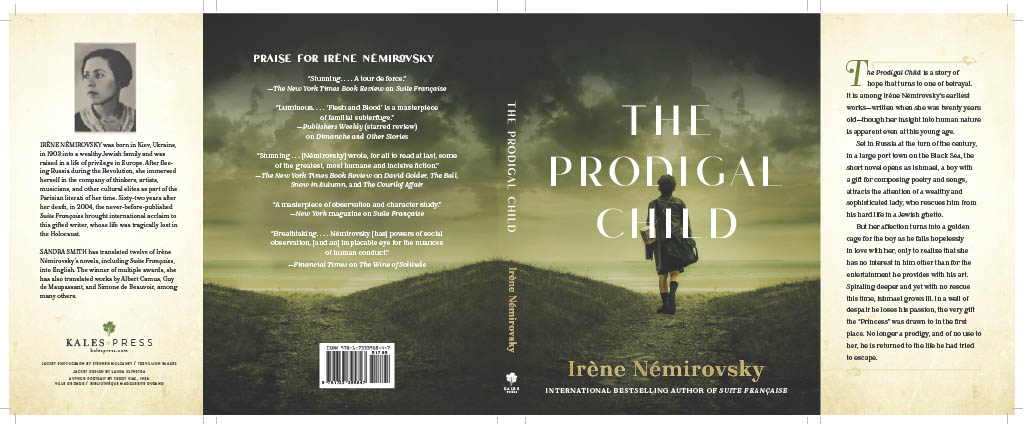

Yara and TJ share a love of photography. He offers to repair her camera and unlocks the derelict back room of the Old Oak, whose walls exhibit his own photos, many taken during the Miners’ Strike of the 1980s (“a whole way of life, just gone forever”). Yara’s open-hearted response to her new home stirs him into action. Together they make plans to use the pub for free meals and social events: “when you eat together, you stick together.”

Of course there are obstacles in the way of peace and love – hatred, stupidity, sabotage and death all threaten to drag TJ down to rock bottom once again.

Two wonderfully warm and human central performances steer the film through the occasional scene that doesn’t quite ring true. Dave Turner is a gentle giant of a man, whose lived-in face conveys stoic vulnerability, pain and pride. Like the Old Oak itself, he is worn out and in need of repair. Yara is the tonic he needs to keep going. Ebla Mari brings a quiet charisma to the role. She has extraordinary eyes, and the kind of unaffected beauty that the camera loves. Hollywood will surely come calling.

Turner, a fire-fighter for 30 years, had been an extra in Loach’s previous two films, but describes himself as a ’non-actor.’ In interviews he talks about feeling “crippling anxiety and imposter syndrome” when filming began for The Old Oak. The make-up lady and ‘unique’ supportive on-set atmosphere helped him through.

‘Strength. Solidarity. Resistance’ reads the community’s splendid banner at the Durham Miners’ Gala, shown at the end of the film. Held proudly by former miners and the Syrian refugees who created it.